Most of us, when we think of guerilla tactics, draw up an image of either sweltering jungles or hot dry cities. Unfortunately not many of the regions we currently live in mirror the Mekong Delta or Tikrit. For this reason I keep my ears open for other military engagements with which we can draw more applicable lessons. I understand that there is a very critical relationship between militants and local citizenry in any guerilla style endeavors, but that is not for today’s history lesson. As you read take note of how a smaller force was able to battle a larger and better equipped force; not unlike the actions of our own Revolutionary War over 200 years ago.

if reading is not your style then try out this great documentary on YouTube: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WR2FqMUVZzc.

This is an amazing war that has been largely forgotten by the world as it overlapped with the actions of the much more studied and well known WW II. How would the Finnish army of just over 300,000 men, 32 outdated tanks, and 114 out dated aircraft take on the Russian army attacking with nearly 1 million troops, 6,541 tanks, and 3,880 aircraft? The result would be a roughly five to one casualty ratio in favor of the Finns, and a near complete loss of committed Russian tanks.

The Finns knew that in any war with the USSR, they would be on the defensive; but they vowed that it should be active defense. They were light on firepower, but very good in terms of mobility and lower level tactics. The forest itself dictated a heavy emphasis on individual initiative, and small unit operations, quasi guerilla style. Marksmanship, metal agility, woodcraft, orienteering, camouflage, and physical fitness were all stressed. And parade ground compliments were discouraged. Unconventional tactics, ambushes, long range patrols, deceptions, raids, were enshrined as doctrine and refined.

The Winter War was a military conflict between the Soviet Union and Finland in 1939–1940. It began with the Soviet invasion of Finland on 30 November 1939 (three months after the outbreak of World War II), and ended with the Moscow Peace Treaty on 13 March 1940. The League of Nations deemed the attack illegal and expelled the Soviet Union from the League on 14 December 1939.

(Major Soviet offensives from 30 November – 22 December 1939)

The Soviet Union sought principally to claim parts of Finnish territory, demanding—amongst other concessions—that Finland cede substantial border territories in exchange for land elsewhere, claiming security reasons, primarily the protection of Leningrad, which was only 30 km (19 mi) from the Finnish border. Finland refused and the USSR invaded the country. Some sources assert that the Soviet Union had intended to conquer all of Finland, and use the establishment of the Finnish Communist puppet government as proof of this. Other sources argue that there is no documentary evidence to support this and that there are arguments against the idea of a full Soviet conquest.

(Russian troops cross the boarder)

The Soviets possessed more than three times as many soldiers as the Finns, thirty times as many aircraft, and a hundred times as many tanks. The Red Army, however, had been crippled by Soviet leader Joseph Stalin’s Great Purge of 1937. With more than 30,000 of its officers executed or imprisoned, including most of those of the highest ranks, the Red Army in 1939 had many inexperienced senior and mid-level officers. Because of these factors, and high morale in the Finnish forces, Finland repelled Soviet attacks for several months, much longer than the Soviets expected.

First battles

The Mannerheim Line, an array of Finnish defence structures, was located on the Karelian Isthmus about 30 to 75 km (19 to 47 mi) from the Soviet border. The Red Army soldiers on the Isthmus numbered 250,000 facing 130,000 Finns. The Finnish command deployed a covering force of about 21,000 men in the area in front of the Mannerheim Line in order to delay and damage the Red Army before it reached the line.

In combat, the biggest cause of confusion among Finnish soldiers were Soviet tanks. The Finns had few anti-tank weapons and insufficient training in modern anti-tank tactics. However, the favored Soviet armored tactic was a simple frontal charge, the weaknesses of which could be exploited. The Finns learned that at close range, tanks could be dealt with in many ways; for example, logs and crowbars jammed into the bogie wheels would often immobilize a tank. Soon, Finns fielded a better ad hoc weapon, the Molotov cocktail. It was a glass bottle filled with flammable liquids, with a simple hand-lit fuse. Molotov cocktails were eventually mass-produced by the Finnish Alko corporation and bundled with matches with which to light them. Eighty Soviet tanks were destroyed in the border-zone fighting.

By 6 December, all the Finnish covering forces had withdrawn to the Mannerheim Line. The Red Army began its first major attack against the Line in Taipale—the area between the shore of Lake Ladoga, the Taipale river and the Suvanto waterway. Along the Suvanto sector, the Finns had a slight advantage of elevation and dry ground to dig into. The Finnish artillery had scouted the area and made fire plans in advance, anticipating a Soviet assault. The Battle of Taipale began with a forty-hour Soviet artillery preparation. After the barrage, the Soviet infantry attacked across open ground but was repulsed with heavy casualties. From December 6 to 12, the Red Army continued trying to engage using only one division. The Red Army next strengthened its artillery and brought tanks and the 10th Rifle Division to the Taipale front. On 14 December, the bolstered Soviet forces launched a new attack but were pushed back again. A third Soviet division entered the fight but performed poorly and panicked under shell fire. The assaults continued without success, and the Red Army suffered heavy losses. One typical Soviet attack during the battle lasted just an hour but left 1,000 dead and 27 tanks strewn on the ice.

(Destroyed Russian KV-1 Tank)

North of Lake Ladoga on the Ladoga Karelia front, the defending Finnish units relied on the terrain. Ladoga Karelia, as a large forest wilderness, did not have road networks for the modern Red Army. However, the Soviet 8th Army had extended a new railroad line to the border, which could double the supply capability on the front. But on 12 December, the advancing Soviet 139th Rifle Division, supported by the 56th Rifle Division, was defeated by a much smaller Finnish force under Paavo Talvela in Tolvajärvi, the first Finnish victory of the war.

In central and northern Finland, roads were few and the terrain hostile. The Finns did not expect large-scale Soviet attacks, but the Soviets sent eight divisions, heavily supported by armor and artillery. The 155th Rifle Division attacked at Lieksa, and further north the 44th attacked at Kuhmo. The 163rd Rifle Division was deployed at Suomussalmi and charged with cutting Finland in half by marching the Raate Road. In Finnish Lapland, the Soviet 88th and 122nd Rifle Divisions attacked at Salla. The Arctic port of Petsamo was attacked by the 104th Mountain Rifle Division by sea and land, supported by naval gunfire.

Weather conditions

The winter of 1939–1940 was exceptionally cold. One location on the Karelian Isthmus experienced a record low temperature of −43 °C (−45 °F) on 16 January 1940. At the beginning of the war, only those Finnish soldiers who were in active service had uniforms and weapons. The rest had to make do with their own clothing, which for many soldiers was their normal winter clothing with semblance of an insignia added. Finnish soldiers were skilled in cross-country skiing.

The cold, snow, forest, and long hours of darkness were factors that the Finns could use to their advantage. The Finns dressed in layers, and the ski troopers wore a lightweight white snow cape. This snow-camouflage made the ski troopers almost invisible as the Finns executed guerrilla attacks against Soviet columns. At the beginning of the war, Soviet tanks were painted in standard olive drab and men dressed in regular khaki uniforms. Not until late January 1940 did the Soviets paint their equipment white and issue snowsuits to their infantry.

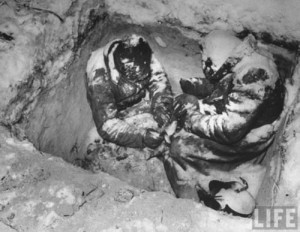

Most Soviet soldiers had proper winter clothes, but this was not the case with every unit. In the battle of Suomussalmi, many Soviet soldiers died of frostbite. Furthermore, the Soviet troops lacked skill in skiing, so soldiers were restricted to movement by road and were forced to move in long columns. Furthermore, the Red Army lacked proper winter tents, and men had to sleep in improvised shelters. Some Soviet units had frostbite casualties as high as 10% even before crossing the Finnish border. The cold weather did confer one advantage: Soviet tanks were able to move more easily over frozen terrain and bodies of water, rather than being immobilized in swamps and mud.

(Russian soldiers dead of exposure)

Before the Winter War, no army had fought in such freezing conditions. In Soviet field hospitals, operations were done and limbs were amputated at −20 °C (−4 °F) while just past the canvas tent wall the temperature was −30 °C. Injured Finnish soldiers could expect a heated operating room. This improved their fighting abilities while hampering Soviet soldiers.

Finnish tactics

In battles from Ladoga Karelia all the way north to the Arctic port of Petsamo, the Finns used guerrilla tactics. The Red Army was superior in numbers and materiel, but the Finns used the advantages of speed, tactics, and economy of force. Particularly on the Ladoga Karelia front and during the battle of Raate road, the Finns isolated smaller portions of numerically superior Soviet forces. With Soviet forces divided into smaller pieces, the Finns could deal with them individually and attack from all sides.

For many of the encircled Soviet troops in a pocket, (motti in Finnish, motti also means a bundle of wood), just staying alive was an ordeal comparable to combat. The men were freezing and starving and endured poor sanitary conditions. Historian William R. Trotter describes these conditions thus: “The Soviet soldier had no choice. If he refused to fight, he would be shot. If he tried to sneak through the forest, he would freeze to death. And surrender was no option for him; Soviet propaganda had told him how the Finns would torture prisoners to death.”

The Finnish sniper Simo Häyhä was nicknamed “White Death” by the Soviets. He is credited with killing over 500 enemy soldiers, using a Mosin-Nagant rifle. In March 1940 he was shot through the jaw, but lived through the injury.

Defense of the Mannerheim Line

The terrain on the Karelian Isthmus did not allow the exercise of guerilla tactics, so the Finns were forced to resort to the more conventional Mannerheim Line, with its flanks protected by large bodies of water. Soviet propaganda claimed that it was as strong as or even stronger than the Maginot Line. Finnish historians, for their part, have belittled the line’s strength, insisting that it was mostly conventional trenches and log-covered dugouts.

The Finns had built 221 strongpoints along the Karelian Isthmus, mostly in the early 1920s. Many were extended in the late 1930s. Despite these defensive preparations, even the most fortified section of the Mannerheim Line had only one reinforced concrete bunker per kilometer. Overall, the line was weaker than similar lines in mainland Europe. According to the Finns, the real strength of the line were the “stubborn defenders with a lot of sisu” – a Finnish idiom roughly translated as “guts, fighting spirit.”

On the eastern side of the isthmus, the Red Army attempted to break through the Mannerheim Line in the battle of Taipale. On the western side, Soviet units faced the Finnish line at Summa, near the city of Viipuri, on 16 December. The Finns had built 41 reinforced concrete bunkers in the Summa area, making the defensive line in this area stronger than anywhere else on the Karelian Isthmus. However, because of a mistake in planning, the nearby Munasuo swamp had a 1 km (0.62 mi)-wide gap in the line. During the first battle of Summa, a number of Soviet tanks broke through the thin line on 19 December, but the Soviets could not benefit from the situation because of insufficient cooperation between branches of service. The Finns remained in their trenches, allowing the Soviet tanks to move freely behind the Finnish line, as the Finns had no proper anti-tank weapons. However, the Finns succeeded in repelling the main Soviet assault. The tanks, stranded behind enemy lines, attacked the strongpoints at random until they were eventually destroyed, 20 in all. By 22 December, the battle ended in a Finnish victory.

The Soviet advance was stopped at the Mannerheim Line. Red Army troops suffered from poor morale and a shortage of supplies, eventually refusing to participate in more suicidal frontal attacks. The Finns, led by General Harald Öhquist, decided to launch a counterattack and encircle three Soviet divisions into a motti near Viipuri on 23 December. Öhquist’s plan was bold, but it failed. The Finns lost 1,300 men, and the Soviets were later estimated to have lost a similar number.

Battles in Ladoga Karelia

The strength of the Red Army north of Lake Ladoga (in Ladoga Karelia) surprised the Finnish General Staff. Two Finnish divisions were deployed there: the 12th Division led by Lauri Tiainen and the 13th Division led by Hannu Hannuksela. They also had a support group of three brigades, bringing their total strength to over 30,000. The Soviets deployed a division for almost every road leading west to the Finnish border. The Eighth Army was led by Ivan Khabarov, who was replaced by Grigori Shtern on 13 December. The Soviets’ mission was to destroy the Finnish troops in the area of Ladoga Karelia and advance into the area between Sortavala and Joensuu within 10 days. The Soviets had a 3:1 advantage in manpower and 5:1 advantage in artillery as well as air supremacy.

Finnish forces panicked and retreated in front of the overwhelming Red Army. The commander of the Finnish IV Army Corps was replaced by Woldemar Hägglund on 4 December. On 7 December, in the middle of the Ladoga Karelian front, Finnish units retreated near the small stream of Kollaa. The waterway itself did not offer protection, but alongside there were ridges up to 10 m (33 ft) high. The battle of Kollaa lasted until the end of the war. A memorable quote, “Kollaa holds” (Finnish: Kollaa kestää) became a legendary motto among the Finns. Further contributing to the legend of Kollaa was the sniper Simo Häyhä, dubbed “the White Death” by Soviets, who served in the Kollaa front. To the north, the Finns retreated from Ägläjärvi to Tolvajärvi on 5 December and then repelled a Soviet offensive in the battle of Tolvajärvi on 11 December.

In the south, two Soviet divisions were united on the northern side of the Lake Ladoga coastal road. As before, these divisions were trapped as the more mobile Finnish units were able to counterattack from the north to flank the Soviet columns. On 19 December, the Finns temporarily ceased their assaults, as the soldiers were exhausted. It was not until the period 6–16 January 1940 that the Finns went on the offensive again, cutting Soviet division into smaller groups of different-sized mottis.

(Finnish soldier with an M26 machine gun)

Contrary to Finnish expectations, the encircled Soviet divisions did not try to break through to the east but instead entrenched. They were expecting reinforcements and supplies to arrive by air. As the Finns lacked the necessary heavy artillery equipment and were short of men, they often did not directly attack mottis they had created; instead, they focused on eliminating only the most dangerous threats. Often the motti tactic was not part of pre-planned doctrine but a Finnish adaptation to the behavior of Soviet troops under fire.

In spite of the cold and hunger, the Soviet troops did not surrender easily but fought bravely, often entrenching their tanks to be used as pillboxes and building timber dugouts. Some specialist Finnish soldiers were called in to attack the mottis; the most famous of them was Major Matti Aarnio, or “Motti-Matti,” as he became known.

(Dead Russian soldiers)

In northern Karelia, Soviet forces were outmaneuvered at Ilomantsi and Lieksa. The Finns used effective guerrilla tactics, taking special advantage of superior skiing skills and snow-white layered clothing and executing many surprise ambushes and raids. By the end of December, the Soviets decided to retreat and transfer resources to more critical fronts.

Suomussalmi–Raate double operation

The Suomussalmi–Raate was a double operation, which would later be used by military academics as a classic example of what well-led troops and innovative tactics can do against a much larger adversary. Suomussalmi was a small provincial town of 4,000. The area has long lakes, many wild forests and few roads. The Finnish command believed that the Soviets would not attack here, but the Red Army committed two divisions to the area with orders to cross the wilderness, capture the city of Oulu and effectively cut Finland in two. There were two roads leading to Suomussalmi from the frontier: the northern Juntusranta road and the southern Raate road.

The battle of Raate road, which occurred during the month-long battle of Suomussalmi, resulted in one of the largest losses in the Winter War. The Soviet 44th and parts of the 163rd Rifle Divisions, comprising about 14,000 troops, were almost completely destroyed by a Finnish ambush as they marched along the forest road. A small unit blocked the Soviet advance while Finnish Colonel Hjalmar Siilasvuo and his 9th Division cut off the retreat route, split the enemy force into smaller fragments, and then proceeded to destroy the remnants in detail as they retreated. The Soviets suffered 7,000–9,000 casualties, while the Finnish units lost only 400 men. In addition, the Finnish troops captured dozens of tanks, artillery pieces, anti-tank guns, hundreds of trucks, almost 2,000 horses, thousands of rifles, and much-needed ammunition and medical supplies.

(Russian dead along the road)

Finnish Lapland

In Finnish Lapland, the forests gradually thin out until in the north there are no trees at all. Thus, the area offers more room for tank deployment, but it is vastly underpopulated and experiences copious snowfall. The Finns expected nothing more than raiding parties and reconnaissance patrols, but instead the Soviets sent full divisions. On 11 December, the Finns rearranged the defense of Lapland and detached the Lapland Group from the North Finland Group. The group was placed under the command of Kurt Wallenius.

In southern Lapland, near the tiny rural village of Salla, the Soviet force advanced with two divisions, the 88th and 112th, totaling 35,000 men. In the battle of Salla the Soviets advanced easily to Salla, where the road forked. The northern branch moved toward Pelkosenniemi while the rest pushed on toward Kemijärvi. On 17 December, the Soviet northern group, comprising an infantry regiment, a battalion, and a company of tanks, was outflanked by a Finnish battalion. The 112th retreated, leaving much of its heavy equipment and vehicles behind. Following this success, the Finns shuttled reinforcements down to the defensive line in front of Kemijärvi. The Soviets hammered the defensive line without success. The Finns counterattacked, and the Soviets were pushed back to a new defensive line where they stayed for the rest of the war.

(Finnish machine gunners)

To the north was Finland’s only ice-free port in the Arctic, Petsamo. The Finns did not have the manpower to defend it fully as the main front was down the Karelian Isthmus. In the battle of Petsamo, the Soviet 104th division attacked the Finnish 104th Independent Cover Company. The Finns gave up Petsamo easily and concentrated on delaying actions. The area was treeless, windy, and relatively low, offering little defensible terrain. However, during the winter, the Finns in Lapland had the advantage of almost constant darkness and extreme temperatures. The Finns executed guerrilla attacks against Soviet supply lines and patrols. As a result, the Soviet movements were halted by the efforts of one-fifth as many Finns.

Conclusion

After reorganization and adoption of different tactics, the renewed Soviet offensive overcame Finnish defenses at the borders. Finland then agreed to cede the territory originally demanded by the Soviet Union; the Soviets, having lost far more troops than anticipated, accepted this offer.

Hostilities ceased in March 1940 with the signing of the Moscow Peace Treaty. Finland ceded territory representing 11% of its land area and 30% of its economy to the Soviet Union. Soviet losses were heavy, and the country’s international reputation suffered. While the Soviet Union did not conquer all Finland, Soviet gains somewhat exceeded their pre-war demands. They gained substantial territory along Lake Ladoga, providing a buffer for Leningrad, and territory in northern Finland. Finland retained its sovereignty and enhanced its international reputation.

Leave a Reply