So; for Christmas we drove down to the California LA area to visit my wife’s family. While there we went on several walks into the hills after meals, especially when the kids needed to get out of the house. They told me about the abundance of poison oak in the area and how one of their sons had been horrible affected at least seven times. I looked into those mysterious scrub growth forests and realized I was used to the plants of the northwest states and was completely unfamiliar with these areas. Having run into little more than stinging nettle while camping I grew increasingly spooked when they said leaves on the ground could affect you as well as the branches devoid of leaves in the winter months. Needless to say I had to do a little more research and bring myself up to speed with the common poisonous plants of North America; and being on vacation and lacking all my good reading material from home I turned to my favorite online start point, Wikipedia, and found most of what I was looking for. Attached are some photos, summaries, and excerpts. Some plants, I was surprised to learn, actually had useful traits; and, according to my wife’s family, early native peoples in the area would actually expose parts of their arms repeatedly to the poison oak and then wrap it to prevent its spreading, as a form of inoculation. I guess if Rasputin can inoculate himself to cyanide, it can be done with stinging nettle; for my part I’m just gonna avoid the crap.

Jon

Poison Ivy:

Toxicodendron radicans, commonly known as poison ivy is a poisonous North American and Asian plant that is well known for its production of urushiol, a clear liquid compound in the sap of the plant that causes an itching, irritation and sometimes painful rash in most people who touch it; however, the plant is not a true ivy (Hedera).

Poison ivy can be found growing in any of the following forms: as a trailing vine that is 10–25 centimetres (3.9–9.8 in) tall, as a shrub up to 1.2 metres (3 ft 11 in) tall, and as a climbing vine that grows on trees or some other support.

The following four characteristics are sufficient to identify poison ivy in most situations: (a) clusters of three leaflets, (b) alternate leaf arrangement, (c) lack of thorns, and (d) each group of three leaflets grows on its own stem, which connects to the main vine.

Below are some clever phrases to help you with identifying this particular plant:

“Leaflets three; let it be” is the best known and most useful cautionary rhyme. It applies to poison oak, as well as to poison ivy.

“Hairy vine, no friend of mine.”

“Longer middle stem, stay away from them.” This refers to the middle leaflet having a visibly longer stem than the two side leaflets and is a key to differentiating it from the similar-looking Rhus aromatica (fragrant sumac).

“Raggy rope, don’t be a dope!” Poison ivy vines on trees have a furry “raggy” appearance. This rhyme warns tree climbers to be wary. Old, mature vines on tree trunks can be quite large and long, with the recognizable leaves obscured among the higher foliage of the tree.

“One, two, three? Don’t touch me.”

“Berries white, run in fright” and “Berries white, danger in sight.”

“Red leaflets in the spring, it’s a dangerous thing.” This refers to the red appearance that new leaflets sometimes have in the spring. (Note that later, in the summer, the leaflets are green, making them more difficult to distinguish from other plants, while in autumn they can be reddish-orange.)

“Side leaflets like mittens, will itch like the dickens.” This refers to the appearance of some, but not all, poison ivy leaves, where each of the two side leaflets has a small notch that makes the leaflet look like a mitten with a “thumb.” (Note that this rhyme should not be misinterpreted to mean that only the side leaflets will cause itching, since actually all parts of the plant can cause itching.)

“If it’s got hair, it won’t be fair.” This refers to the hair that can be on the stem and leaves of poison ivy.

In short, there are a variety of plant types that all very slightly, find out what is prevalent in your area and stay clear of it.

Uses:

I could not find any uses for this plant.

Poison Oak:

Toxicodendron diversilobum, commonly named Pacific poison oak or western poison oak (syn. Rhus diversiloba), is in the Anacardiaceae (sumac) family.

The woody vine or shrub is widely distributed in western North America, inhabiting conifer and mixed broadleaf forests, woodlands, grasslands, and chaparral biomes. It is known for causing itching and allergic rashes in many humans, after contact by touch or smoke inhalation.

Toxicodendron diversilobum, Pacific or western poison oak, is extremely variable in growth habit and leaf appearance. It grows as a dense 0.5–4 metres (1.6–13 ft) tall shrub in open sunlight, a treelike vine 10–30 feet (3.0–9.1 m) and may be more than more than 100 feet (30 m) long with an 8–20 cm (3.1–7.9 in) trunk, as dense thickets in shaded areas, or any form in between. It reproduces by spreading rhizomes and by seeds.

The plant is winter deciduous, so that after cold weather sets in, the stems are leafless and bear only the occasional cluster of berries. Without leaves, poison oak stems may sometimes be identified by occasional black marks where its milky sap may have oozed and dried.

The leaves are divided into three (rarely 5, 7, or 9) leaflets, 3.5 to 10 centimetres (1.4 to 3.9 in) long, with scalloped, toothed, or lobed edges. They generally resemble the lobed leaves of a true oak, though the Pacific poison oak leaves will tend to be more glossy. Leaves are typically bronze when first unfolding in February to March, bright green in the spring, yellow-green to reddish in the summer, and bright red or pink from late July to October.

White flowers form in the spring, from March to June. If they are fertilized, they develop into greenish-white or tan berries.

Botanist John Howell observed the toxicity of Toxicodendron diversilobum obscures its merits:

“In spring, the ivory flowers bloom on the sunny hill or in sheltered glade, in summer its fine green leaves contrast refreshingly with dried and tawny grassland, in autumn its colors flame more brilliantly than in any other native, but one great fault, its poisonous juice, nullifies its every other virtue and renders this beautiful shrub the most disparaged of all within our region.”

Uses:

Californian Native Americans used the plant’s stems and shoots to make baskets, the sap to cure ringworm, and as a poultice of fresh leaves applied to rattlesnake bites. The juice or soot was used as a black dye for sedge basket elements, tattoos, and skin darkening.

An infusion of dried roots, or buds eaten in the spring, were taken by some native peoples for an immunity from the plant poisons.

Chumash peoples used Pacific poison-oak sap to remove warts, corns, and calluses; to cauterize sores; and to stop bleeding. They drank a decoction made from Pacific poison-oak roots to treat dysentery.

Poison sumac:

Toxicodendron vernix, commonly known as Poison sumac, is a woody shrub or small tree growing to 9 m (30 ft) tall. It was previously known as Rhus vernix. All parts of the plant contain a resin called urushiol that causes skin and mucous membrane irritation to humans. When burned, inhalation of the smoke may cause the rash to appear on the lining of the lungs, causing extreme pain and possibly fatal respiratory difficulty.

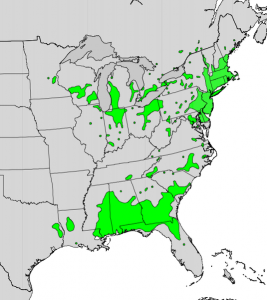

Poison sumac grows exclusively in very wet or flooded soils, usually in swamps and peat bogs, in the eastern United States and Canada.

Uses:

I also found no common use(s) for this plant.

Stinging Nettle:

Urtica dioica, often called common nettle or stinging nettle (although not all plants of this species sting), is a herbaceous perennial flowering plant, native to Europe, Asia, northern Africa, and North America, and is the best-known member of the nettle genus Urtica. The species is divided into six subspecies, five of which have many hollow stinging hairs called trichomes on the leaves and stems, which act like hypodermic needles, injecting histamine and other chemicals that produce a stinging sensation when contacted by humans and other animals. The plant has a long history of use as a medicine, as a food source and as a source of fibre.

Urtica dioica is a dioecious herbaceous perennial, 1 to 2 m (3 to 7 ft) tall in the summer and dying down to the ground in winter. It has widely spreading rhizomes and stolons, which are bright yellow as are the roots. The soft green leaves are 3 to 15 cm (1 to 6 in) long and are borne oppositely on an erect wiry green stem. The leaves have a strongly serrated margin, a cordate base and an acuminate tip with a terminal leaf tooth longer than adjacent laterals. It bears small greenish or brownish numerous flowers in dense axillary inflorescences. The leaves and stems are very hairy with non-stinging hairs and in most subspecies also bear many stinging hairs (trichomes), whose tips come off when touched, transforming the hair into a needle that will inject several chemicals: acetylcholine, histamine, 5-HT (serotonin), moroidin, leukotrienes, and possibly formic acid. This mixture of chemical compounds cause a painful sting or paresthesia from which the species derives one of its common names, stinging nettle, as well as the colloquial names burn nettle, burn weed, and burn hazel.

Uses:

Nettle leaf is a herb that has a long tradition of use as an adjuvant remedy in the treatment of arthritis in Germany. Nettle leaf extract contains active compounds that reduce TNF-α and other inflammatory cytokines. It has been demonstrated that nettle leaf lowers TNF-α levels by potently inhibiting the genetic transcription factor that activates TNF-α and IL-1B in the synovial tissue that lines the joint.

Urtica dioica herb has been used in the traditional Austrian medicine internally (as tea or fresh leaves) for treatment of disorders of the kidneys and urinary tract, gastrointestinal tract, locomotor system, skin, cardio-vascular system, hemorrhage, flu, rheumatism and gout.

Nettle is used in shampoo to control dandruff and is said to make hair more glossy, which is why some farmers include a handful of nettles with cattle feed.

Nettle root extracts have been extensively studied in human clinical trials as a treatment for symptoms of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH). These extracts have been shown to help relieve symptoms compared to placebo both by themselves and when combined with other herbal medicines.

Because it contains 3,4-divanillyltetrahydrofuran, certain extracts of the nettle are used by bodybuilders in an effort to increase free testosterone by occupying sex-hormone binding globulin.

As Old English stiðe, nettle is one of the nine plants invoked in the pagan Anglo-Saxon Nine Herbs Charm, recorded in the 10th century. Nettle is believed to be a galactagogue, a substance that promotes lactation.

Urtication, or flogging with nettles, is the process of deliberately applying stinging nettles to the skin in order to provoke inflammation. An agent thus used is known as a rubefacient (something that causes redness). This is done as a folk remedy for rheumatism, providing temporary relief from pain. The counter-irritant action to which this is often attributed can be preserved by the preparation of an alcoholic tincture which can be applied as part of a topical preparation, but not as an infusion, which drastically reduces the irritant action.

Food:

Urtica dioica has a flavour similar to spinach and cucumber when cooked and is rich in vitamins A, C, iron, potassium, manganese, and calcium. Young plants were harvested by Native Americans and used as a cooked plant in spring when other food plants were scarce. Soaking stinging nettles in water or cooking will remove the stinging chemicals from the plant, which allows them to be handled and eaten without incidence of stinging. After the stinging nettle enters its flowering and seed setting stages the leaves develop gritty particles called “cystoliths”, which can irritate the urinary tract. In its peak season, nettle contains up to 25% protein, dry weight, which is high for a leafy green vegetable. The young leaves are edible and make a very good pot-herb. The leaves are also dried and may then be used to make a tisane, as can also be done with the nettle’s flowers.

Nettles can be used in a variety of recipes, such as polenta, pesto and purée. Nettle soup is a common use of the plant, particularly in Northern and Eastern Europe. In Nepal and the Kumaon & Gargwal region of Northern India, stinging nettle is known as sisnu, kandeli and bicchu-booti (बिच्छू-बूटी in Hindi) respectively. It is also found in abundance in Kashmir. There it is called soi. It is a very popular vegetable and cooked with Indian spices.

Nettles are sometimes used in cheese making, for example in the production of Yarg and as a flavouring in varieties of Gouda.

Nettles are used in Albania as part of the dough filling for the byrek. Its name is byrek me hithra. The top baby leaves are selected and simmered, then mixed with other ingredients like herbs, rice, etc. before being used as a filling between dough layers.

Identify Effects of Poison Plant exposure (from WebMD):

The rash is caused by contact with an oil (urushiol) found in poison ivy, oak, or sumac. The oil is present in all parts of the plants, including the leaves, stems, flowers, berries, and roots. Urushiol is an allergen, so the rash is actually an allergic reaction to the oil in these plants. Indirect contact with urushiol can also cause the rash. This may happen when you touch clothing, pet fur, sporting gear, gardening tools, or other objects that have come in contact with one of these plants. But urushiol does not cause a rash on everyone who gets it on his or her skin.

- The usual symptoms of the rash are:

- Itchy skin where the plant touched your skin.

- Red streaks or general redness where the plant brushed against the skin.

- Small bumps or larger raised areas (hives).

- Blisters filled with fluid that may leak out.

The rash usually appears 8 to 48 hours after your contact with the urushiol. But it can occur from 5 hours to 15 days after touching the plant.1 The rash usually takes more than a week to show up the first time you get urushiol on your skin. But the rash develops much more quickly (within 1 to 2 days) after later contacts. The rash will continue to develop in new areas over several days but only on the parts of your skin that had contact with the urushiol or those parts where the urushiol was spread by touching.

The rash is not contagious. You cannot catch or spread a rash after it appears, even if you touch it or the blister fluid, because the urushiol will already be absorbed or washed off the skin. The rash may seem to be spreading. But either it is still developing from earlier contact or you have touched something that still has urushiol on it.

The more urushiol you come in contact with, the more severe your skin reaction. Severe reactions to smaller amounts of urushiol also may occur in people who are highly sensitive to urushiol. Serious symptoms may include:

- Swelling of the face, mouth, neck, genitals, or eyelids (which may prevent the eyes from opening).

- Widespread, large blisters that ooze large amounts of fluid.

General Treatment (as recommended on wikiHow):

- Remove and wash your clothes. Strip off your clothes and place them in a plastic garbage bag, if possible. Wash your clothes separately from anything else as soon as possible.

- Apply rubbing alcohol. You can apply rubbing alcohol to your skin to dissolve the poison ivy or poison oak oils. Because the toxic oil from the plant seeps into your skin gradually, adding rubbing alcohol to the area will prevent the further spread. It won’t provide immediate relief, but it will stem the spread. You can also use an over-the-counter cleanser like Tecnu or Zanfel.

- Rinse the area with cool water. Never use warm or hot water, as this will open your pores and allow more of the toxins to sink in. If you’re able, keep the affected area under cold running water for 10-15 minutes. If you’re outdoors in the woods when you’re exposed to poison ivy or poison oak, then you can rinse your body off in a running stream.

- Completely clean the area. Regardless of the location on your body, make sure that it was thoroughly rinsed with water. If you touched the area on your body at all or the poison affected your hands, scrub under your fingernails with a toothbrush in case any oil from the plants was deposited beneath them. Throw the toothbrush away after you’re done.

- Use a dish soap that is used for oil removal to rinse the area of your rash. Because the toxins have been transferred to your skin in the form of an oil, using an oil-obliterating dish soap may help to reduce the spread of the rash.

- If you use a towel to dry yourself after washing the affected area, be sure to wash the towel with the rest of your exposed clothes immediately after use.

- Don’t scratch the rash. Even though the rash is not contagious, you could break the skin and allow bacteria to enter the wound. Don’t touch or pop any blisters that may form, even if they are weeping. If necessary, cut your nails short and cover the area to keep yourself from scratching it.

- Cool off the exposed area. Apply cold compresses or apply an icepack for 10 to 15 minutes. Make sure that you don’t apply ice directly to your skin; always wrap your ice pack or compress in a towel before application. Also, allow the area to air dry instead of rubbing it with a towel if you get your rash wet.

Leave a Reply