All the stats in this article deal with commercial airliners, not military or personal aircraft. This article also deals specifically with fixed wing not rotary wing aircraft (that means planes and not helicopters). And if you read all the way to the bottom you’ll find some inside humor if you enjoyed Fight Club.

Ben Sherwood’s The Survivor’s Club, has a superb chapter dedicated to just this topic. If you do not have this book I recommend you procure a copy; and when you read it have a highlighter in hand because the info is worth holding on to. As usual, my references are below for additional reading.

Jon

The Odds

Information can be hard to obtain, and since most every other article quotes from the same 1983-2000 study released by the National Transportation Safety Board; I’m going to also, but I’ve dug up additional information that you will like find interesting and make flight feel more safe

(February 11, 2013)…It will be four years on Tuesday since the last fatal crash in the United States, a record unmatched since propeller planes gave way to the jet age more than half a century ago. Globally, last year (2012) was the safest since 1945, with 23 deadly accidents and 475 fatalities, according to the Aviation Safety Network, an accident researcher. That was less than half the 1,147 deaths, in 42 crashes, in 2000.

In the last five years (2007-20012), the death risk for passengers in the United States has been one in 45 million flights, according to Arnold Barnett, a professor of statistics at M.I.T. In other words, flying has become so reliable that a traveler could fly every day for an average of 123,000 years before being in a fatal crash, he said.

According to National Transportation Safety Board statistics of airplane accidents which occurred between 1983 and 2000, 17 years, 51,207 out of the 53,487 passengers in those accident survived. That’s a 95.7 percent survival rate for those involved in an actual crash. Even when only the most serious 26 accidents are looked at, 1,525 of 2,739 passengers survived. That’s a 56 percent survival rate of the most serious crashes. If we remove the Lockerbie, Scotland crash, which was not an accident, but intentionally caused by a bomb, the survival rate (1983-2000) from serious accidents increases to 61 percent.

In 17 years fewer than 54,000 passengers were involved in a plane accident, yet last year alone (2008), US carriers hauled more than 809 million passengers. The odds of you being in an airplane accident are minuscule; the annual risk of being killed in a plane crash for the average American is about 1 in 11 million.

The odds weren’t always in passengers’ favor. From 1962 to 1981, 54 percent of people in plane crashes were killed. From 1982 to 2009, that figure improved to 39 percent, according to an Associated Press analysis of National Transportation Safety Board data. Those figures only include crashes with at least one fatality which is why they may sound a little off when compared to the numbers above; there have been serious crashes where everybody survived.

The most famous was a US Airways flight in January 2009 that lost engine power after striking a flock of geese after taking off from New York’s LaGuardia Airport. Capt. Chesley B. “Sully” Sullenberger ditched the Airbus A320 in the Hudson River and all 155 people onboard survived. The crash was dubbed the “Miracle on the Hudson.”

This April, a Boeing 737 flown by Indonesian airline Lion Air crashed into water short of a runway in Bali. The plane’s fuselage split into two sections but all 108 people on board survived.

“What’s really important is for people to understand that airplane crashes, the majority of them are survivable,” Deborah Hersman, chairwoman of the National Transportation Safety Board, said on the CBS News show, “Face the Nation.”

Those in the airline industry often say that a person is more likely to die driving to the airport than on a flight. There are more than 30,000 US motor-vehicle deaths each year, a mortality rate eight times greater than that in planes over the expanse of the globe.

What to Do

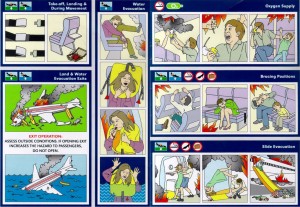

I’m a little odd so here is my routine for flights, and I’ve been on many dozens. First I profile the passengers, no kidding; after several deployments you can’t help but get a feel for the people you’re flying with. Once I sit I find the nearest emergency escape and then count how many rows away it is; figuring that if smoke is in the cabin I can’t rely on line of site to get me out. Lastly I listen to the inflight brief. I am guilty of always taking my shoes off, as long as my socks are clean; and I listen to music the whole way so I don’t have to have conversations with people I don’t know; what can I say, it’s who I am.

Think of the stats above and then consider that according to the European Transport Safety Councel, 40% of fatalities in plane crashes around the world occur in situations that are actually survivable.

Sitting within five rows of any exit improves your likelihood of survival. A British safety expert reviewed seating plans in more than 100 crashes and interviewed nearly 2,000 passengers. He concluded that five rows is the cut-off for likely getting out of a burning plane safely. Beyond that range, your chances of survival drop sharply. Also, passengers in aisle seats have a higher survival rate, than those in window seats.

Did I mention that I always get a window seat if I can? One more thing I do wrong I guess.

Before booking any flights, I check Seat Guru to ascertain seat quality and proximity to exit rows of the available seats on my flights. This is extremely easy in our day as most sites will show you the available seating on a diagram and let you pick and choose either from home or at an airport kiosk.

You may think that how far back you are makes a difference in survivability of a crash; and this idea has abounded in books and the internet, but the truth is crashes are unpredictable and the person sitting next to you is as likely to die and the crash leave you unscathed, as the other way around. But if you never fly first class then go ahead and cite those stats if it give you a warm fuzzy.

Wear the right clothing to fly. Wear a good pair of shoes or leather sneakers, never sandals or flip-flops. For women, wearing high heels may make an airborne fashion statement, but you don’t want to be wearing them in case of an emergency exit from a plane. Sandals or “heels” make it hard to move quickly within wreckage. Wear long pants and long sleeved shirts, made with natural fibers (synthetics or high synthetic content blends can melt on your skin in a fire, causing serious and even fatal wounds) to protect you skin from the possibility of intense heat and fire

Use the “crash position” and brace for impact. Coach seating these days doesn’t give most of us enough room to get our head between our knees. But an alternative is to put your head in your hands and lean against the seat in front of you. “It works,” says Mr. Palmerton. And besides; “You’re hitting the seat whether you want to or not.”

Leave your luggage. As absurd as it sounds, fire-truck videos of real-life emergency evacuations show passengers going down slides clutching belongings — even when the plane is on fire. Smoke can fill a plane in seconds; spend that time getting out, not getting your carry-ons.

Stay low and breathe slowly. Hunched over works best if you can (if you crawl, you might get trampled). And know that breathing aircraft-fire smoke is going to hurt; the slower you breathe, the better.

Get through exits quickly, but one at a time. Doors are small, particularly the exits over the wings; they can easily become clogged with bodies, with deadly consequences. There have been planes on fire where people have died unnecessarily because passengers started fist fights at the escape doors, as with USAir 1493 in February of 1991.

Help at the bottom of a slide if you can. Flight attendants typically ask able-bodied volunteers to assist sliding passengers and have the job of selecting people that look alert and capable to sit in the exit rows. Having someone help you up and move you out prevents piles of people at the bottom — a frequent problem in evacuations — and makes it easier for scared passengers to jump. Videos of real emergency evacuations repeatedly show that volunteers wait only so long before running off themselves.

The biggest threat in a survivable crash is fire. Jet fuel (essentially, kerosene) burns very hot at 1,500°, hotter than the melting point of aluminum. In addition, materials used in manufacturing airplanes give off toxic smoke, so the fuselage can become a deadly gas chamber in as little as 90 seconds. Just as quickly, heat can become so intense that a “flashover” occurs, where the entire cabin explodes in instantaneous combustion.

Bottom line: Get out quickly. To be certified, a commercial airliner has to have enough exits to get a full load of passengers out within 90 seconds, using only half of the doors.

What Airline Companies Have Done

Over the years, planes have become safer. The FAA here, and government aviation authorities elsewhere in the world, have required more and more safety features installed in planes. Many, for example, are to prevent fire in the passenger cabin in case of an accident or an inflight problem in the cargo hold. Thermal insulation, as well as fire suppression systems are now standard in today’s planes.

Passengers in plane crashes today, such as the one in San Francisco involving Asiana Airlines Flight 214, are more likely to survive than in past disasters.

That particular crash was one of the latest where a big commercial airliner was destroyed but most passengers escaped with their lives. There were plenty of cuts, bruises and broken bones — and some more severe injuries — but only 2 of the 307 passengers and crew onboard died.

Regulators started mandating such cabin improvements after two deadly aircraft fires in the 1980s.

First, an Air Canada flight made an emergency landing at Cincinnati’s airport in 1983 after a fire broke out in the bathroom. The plane landed safely but half of the 46 passengers and crew died because they couldn’t quickly escape the smoke and fire.

Two years later, a British Airtours aborted a takeoff in Manchester, England after an engine fire. Passengers evacuated but not fast enough. Of the 137 people onboard, 54 died after inhaling toxic smoke.

“Those two accidents together were the two-by-four to the head” that led the U.S. and British governments to impose new fire-safety standards, said Bill Waldock, a professor of safety science at Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University’s Prescott, Ariz. campus.

Planes now are structurally sounder. In the cabin, stronger seats are less likely to move and crush passengers. Seat cushions and carpeting are fire retardant and doors are easier to open. Those improvements allow people to exit the plane more quickly.

The nature of crashes has also changed. Improvements in cockpit technology mean that planes rarely crash into mountains or each other — accidents that are much more deadly. New technology helps today’s pilots avoid the deadliest types of crashes. Accidents with planes hitting mountains or each other in midair, typically at speeds up to 500 mph, are rare in North America and Europe. Crashes during landing happen while planes are flying at lower speeds of 130 to 150 mph.

“You’ve changed the nature of accidents,” said Capt. Alan W. Price, the former chief pilot for the Atlanta base of Delta Air Lines and founder of consulting firm Falcon Leadership.

Today’s planes come with ground proximity warning systems, which alert pilots if they are too low. An alarm sounds and a computer shouts “terrain, pull up.”

That technology didn’t exist in 1974, when a Trans World Airlines plane heading for Washington Dulles International Airport crashed into 1,754-foot tall Mount Weather in Virginia. All 92 people on board died.

Modern cockpit radar systems alert pilots to other planes nearby. Such a system would have probably prevented the 1960 midair collision of a TWA jet with a United plane over New York, killing all 128 people on the two planes and 6 people on the ground.

Better radar systems on the ground have also helped. They’ve prevented planes from going down the wrong taxiway or onto active runways. The deadliest aviation disaster in history remains the collision of Pan Am and KLM jets on the runway of Tenerife in Spain’s Canary Islands in 1977. In foggy conditions, amid confusion over air traffic controller instructions, the KLM plane took off while the Pan Am jet was taxing down the same runway. The crash killed 583 people on both planes; 61 survived. Had such radar existed at the time, the KLM pilots would have probably seen the Pan Am jet in its way.

“Crashes are definitely more survivable today than they were a few decades ago,” said Kevin Hiatt, president and CEO of the Flight Safety Foundation, an industry-backed nonprofit group aimed at improving air safety. “We’ve learned from the past incidents about what can be improved.”

A British Airways flight in January 2008 crashed short of the runway at London’s Heathrow Airport. All 152 passengers and crew onboard the Boeing 777 — the same jet type as the Asiana flight — survived.

— Stronger seats. Today’s airplane seats — and the bolts holding them into the floor — are designed to withstand forces up to 16 times that of gravity. That prevents rows of seats from pancaking together during a crash, crushing passengers.

— Fire retardant materials. Carpeting and seat cushions are now made of materials that burn slower, spread flames slower and don’t give off noxious and dangerous gases.

— Improved exits. Doors on planes are much simpler to open and easily swing out of the way, allowing passengers to quickly exit. And planes now come with rows of lights on the floor that change from white to red when an exit is reached.

— Better training. Flight attendants at many airlines now train in full-size models of planes that fill with smoke during crash simulations.

— Stronger planes. Aircraft engineers have looked at structural weaknesses from past crashes and reinforced those sections of the plane.

The emergency response also plays a part in limiting the number of fatalities. Airport fire departments frequently hold drills where crews simulate a crash and practice coordinating with area hospitals on how to care for the injured.

Today, thanks to these advances there are about two deaths worldwide for every 100 million passengers on commercial flights, according to an Associated Press analysis of government accident data.

Just a decade ago, passengers were 10 times as likely to die when flying on an American plane. The risk of death was even greater during the start of the jet age, with 1,696 people dying — 133 out of every 100 million passengers — from 1962 to 1971. The figures exclude acts of terrorism.

To Make You Smile:

Consumer Traveler: What are the odds of my plane crashing? May 4, 2009

Fox News: Safety advances boost plane crash survival odds, July 08, 2013

Ewatravel: The Surprising Odds of Surviving a Crash

The New York Times: Airline Industry at Its Safest Since the Dawn of the Jet Age, February 11, 2013

Leave a Reply