I was watching Snow Piercer the other day and thought the ending was pretty cool. I love the whole Asiatic Inuit look to the survivors and the polar bear in the arctic setting. The whole scene made me think about the Inuit culture that did, and still to some degree, exists in the harsh north. A people who have survived the world’s harshest climate zones and prospered. I first really began studying them when researching the lost Viking colonies of Greenland (named such because it was discovered during one of several medieval warm periods and was in fact quite green at the time). The inability of the Vikings to adapt to the Inuit lifestyle was one of many contributing factors to their demise as the climate grew colder; a time when the Inuit, according to archeological research, actually had such an abundance of food they were only eating the choicest parts of hunted and fished animals.

Not that we are heading towards an impending ice age; although climatologists can’t decide if we are heading towards another ice age or another warming period (I say another because we go through them in relatively predictable cycles). But there is something to be said about the skills and abilities of those peoples that populate the permafrost regions of the arctic. What can we learn and take from their way of life? Most of us do not live in the frozen reaches of the north; but their skills might save you if something goes wrong during the winter. How many power outages occur during horrendous blizzards? Have you ever been stranded in your house for a week because four feet of snow fell overnight and shut down the roads (yes that happened to my family once). Not only the Vikings, but what other pioneer groups might have benefitted from a portion of Inuit knowledge? Just food for thought.

Natives of the New World have such an abundance of skills and knowledge to offer. If you have Native American tribes with a long heritage in your area befriend and learn from them. They know tips for keeping you alive in your local biome. I was astounded by the knowledge of a Navajo friend from the four corners area. If I got lost in the high desert I would want to know what he knew. From the Inuit up North we might learn how to build igloos or make warm winter clothing; from the lower Rockies you might learn basic trapping to flint/obsidian knapping for your own tools. If you have a chance to visit Native American gatherings take the opportunity and make some new friends.

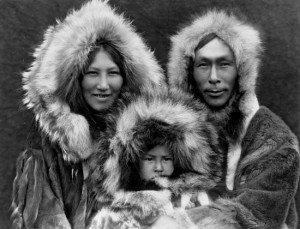

So who are the Inuit? The Inuit are a group of culturally similar indigenous peoples inhabiting the Arctic regions of Greenland, Canada, and the United States. Inuit is a plural noun; the singular is Inuk. The Inuit languages are classified in the Eskimo-Aleut family.

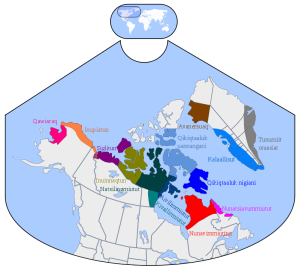

The Inuit live throughout most of the Canadian Arctic and subarctic in the territory of Nunavut; “Nunavik” in the northern third of Quebec; “Nunatsiavut” and “NunatuKavut” in Labrador; and in various parts of the Northwest Territories, particularly around the Arctic Ocean. These areas are known in Inuktitut as the “Inuit Nunangat”. In the United States, Inupiat live on the North Slope in Alaska and on Little Diomede Island. The Greenlandic Inuit are the descendants of migrations from Canada and are citizens of Denmark, although not of the European Union.

Diet

The Inuit have traditionally been fishers and hunters. They still hunt whales (esp. bowhead whale), walrus, caribou, seal, polar bears, muskoxen, birds, and fish and at times other less commonly eaten animals such as the Arctic Fox. The typical Inuit diet is high in protein and very high in fat – in their traditional diets, Inuit consumed an average of 75% of their daily energy intake from fat. While it is not possible to cultivate plants for food in the Arctic, the Inuit have traditionally gathered those that are naturally available. Grasses, tubers, roots, stems, berries, and seaweed (kuanniq or edible seaweed) were collected and preserved depending on the season and the location. There is a vast array of different hunting technologies that the Inuit used to gather their food.

In the 1920s anthropologist Vilhjalmur Stefansson lived with and studied a group of Inuit. The study focused on the fact that the Inuit’s low-carbohydrate diet had no adverse effects on their health, nor indeed, Stefansson’s own health. Stefansson (1946) also observed that the Inuit were able to get the necessary vitamins they needed from their traditional winter diet, which did not contain any plant matter. In particular, he found that adequate vitamin C could be obtained from items in their traditional diet of raw meat such as Ringed Seal liver and whale skin (muktuk). While there was considerable skepticism when he reported these findings, they have been borne out in recent studies and analyses. However, the Inuit have lifespans 12 to 15 years shorter than the average Canadian’s, which is thought to be a result of limited access to medical services. The life expectancy gap is not closing.

Transport, navigation, and dogs

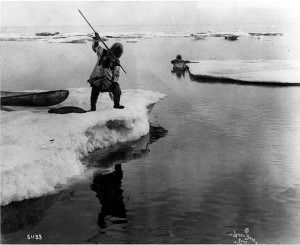

The natives hunted sea animals from single-passenger, covered seal-skin boats called qajaq which were extraordinarily buoyant, and could easily be righted by a seated person, even if completely overturned. Because of this property the design was copied by Europeans and Americans who still produce them under the Inuit name kayak.

Inuit also made umiaq (“woman’s boat”), larger open boats made of wood frames covered with animal skins, for transporting people, goods and dogs. They were 6–12 m (20–39 ft) long and had a flat bottom so that the boats could come close to shore. In the winter, Inuit would also hunt sea mammals by patiently watching an aglu (breathing hole) in the ice and waiting for the air-breathing seals to use them. This technique is also used by the polar bear, who hunts by seeking holes in the ice and waiting nearby.

In winter, both on land and on sea ice, the Inuit used dog sleds (qamutik) for transportation. The husky dog breed comes from Inuit breeding of dogs and wolves for transportation. A team of dogs in either a tandem/side-by-side or fan formation would pull a sled made of wood, animal bones, or the baleen from a whale’s mouth and even frozen fish, over the snow and ice. The Inuit used stars to navigate at sea and landmarks to navigate on land; they possessed a comprehensive native system of toponymy. Where natural landmarks were insufficient, the Inuit would erect an inukshuk.

Dogs played an integral role in the annual routine of the Inuit. During the summer they became pack animals, sometimes dragging up to 20 kg (44 lb) of baggage and in the winter they pulled the sled. Yearlong they assisted with hunting by sniffing out seals’ holes and pestering polar bears. They also protected the Inuit villages by barking at bears and strangers. The Inuit generally favored, and tried to breed, the most striking and handsome of dogs, especially ones with bright eyes and a healthy coat. Common husky dog breeds used by the Inuit were the Canadian Eskimo Dog, the official animal of Nunavut, (Qimmiq; Inuktitut for dog), the Greenland Dog, the Siberian Husky and the Alaskan Malamute. The Inuit would perform rituals over the newborn pup to give it favorable qualities; the legs were pulled to make them grow strong and the nose was poked with a pin to enhance the sense of smell.

Industry, art, and clothing

Inuit industry relied almost exclusively on animal hides, driftwood, and bones, although some tools were also made out of worked stones, particularly the readily worked soapstone. Walrus ivory was a particularly essential material, used to make knives. Art played a big part in Inuit society and continues to do so today. Small sculptures of animals and human figures, usually depicting everyday activities such as hunting and whaling, were carved from ivory and bone. In modern times prints and figurative works carved in relatively soft stone such as soapstone, serpentinite, or argillite have also become popular.

Inuit made clothes and footwear from animal skins, sewn together using needles made from animal bones and threads made from other animal products, such as sinew. The anorak (parka) is made in a similar fashion by Arctic peoples from Europe through Asia and the Americas, including the Inuit. The hood of an amauti, (women’s parka, plural amautiit) was traditionally made extra large with a separate compartment below the hood to allow the mother to carry a baby against her back and protect it from the harsh wind. Styles vary from region to region, from the shape of the hood to the length of the tails. Boots (mukluk or kamik), could be made of caribou or seal skin, and designed for men and women.

During the winter, certain Inuit lived in a temporary shelter made from snow called an iglu, and during the few months of the year when temperatures were above freezing, they lived in tents, known as tupiq, made of animal skins supported by a frame of bones or wood. Some, such as the Siglit, used driftwood, while others built sod houses.

For further reading go to: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Inuit

An Inuit Eskimo Hunter Patiently

[…] still hunt whales (esp. bowhead whale), walrus, caribou, seal, polar bears, musk […]