We found these little tasty roots as kids growing in the fields. We got curious because they smelled like carrots when we dug them up. The taste was similar but had a little more of a radish type bite to it. This post will outline wild carrots (Queen Anne’s Lace), poison hemlock, and some tips for identifying one from the other. As usual, references are at the bottom. Do a little research however so you eat wild carrots and not life threatening poison.

Queen Anne’s Lace

Daucus Carota & Pusillus: Edible Wild Carrots

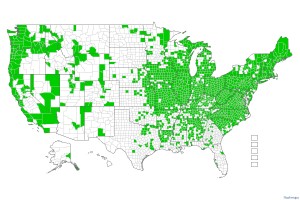

Wild carrots are not located exclusively to the listed locations on the map, these are only the areas where they have been “identified” to be growing.

Queen Anne’s Lace has a flat white blossom with a red spot in the middle, hairy stems and stalk, and the white root that smells like carrot. As the blossom ages it folds up looking like a bird’s nest. Wild carrots were a common pasture plant. The key is to find them at the end of their first year before the roots grow woody their second year. However, often that woody part can be peeled off and the root made edible.

Dacus carota root

Wild Carrot only occasionally has a red flower in the middle. That said, the above description is for the Daucus carota (DAW-kus ka-ROT-a) a wild carrot imported from the Old World and known everywhere in the United States as “Queen Anne’s Lace.” But, there was a native carrot in North America when the Pilgrims arrived, the Daucus pusillus and it does not have a red dot.

Dacus pusillus is found in the southern half of the United States and up the west coast to British columbia. Much smaller than the D. carota, its root are none the less edible, though that is not saying much. It tends to have flowers that are white to pink and white, again no red dot. Like the import, the stems are hairy. The hairy stems and stalk is a very important identification element and separates the two carrots from very deadly members of the same family, such as Poison Hemlock which has a hairless stalk and will be discussed further down.

The Daucus carota is losing some of its luster. A majority of states (at least 35 of them) list it as a pest or a noxious weed. It is particularly bad in Missouri. Apparently D. carota germinates easily and mowing doesn’t get rid of it. Some say the dried seed heads are a fire hazard and a threat to the honey industry.

Daucus pusillus, also called the American Wild Carrot and Rattlesnake Weed is a simple too few-branched annual that grows to three feet tall but usually less. The stems are covered with stiff hairs. The leaves are alternate, pinnate and compound on stems to six inches long. The umbrella-arranged flowers have five white petals and five stamens. It has fewer florets per cluster than the D. carota, 5 to 12, instead of 20. It likes dry ground, rocky to sandy soil, oak forests. Blooming time is April to June. The roots are similar to the D. carota, just smaller.

Unlike many native plants there’s not much evidence most Native Americans made much use of the D. pusillus. Eastern tribes ignored it, perhaps, records on them are scant. Only six western Indians seem to have used it. The Nez Perce and Navajo ate the roots, boiled or raw. They also used it to ‘clean the blood,’ stop itching, and treat fevers. A decoction and or a chewed poultice was used to treat snake bite. The Clallam, Cowichan, Saanich and coastal Salish also ate the root.

One way to get a steady source of good wild carrot roots is to grow them yourself. They sprout readily. Collect the seeds in the fall and set them out in the spring. Under cultivation they grow large, tender roots. The root of Queen Anne’s Lace is likely a direct ancestor of the modern carrot which has been under cultivation for some 5,000 years, probably starting in Afghanistan. While the wild carrot root is cream colored to light orange there are a number of varieties including white, yellow, red, purple, green, black, striped and purple on the outside and orange inside. The orange carrot is believed to have been developed in the 16th century in Holland, where patriotic plant breeders developed it to celebrated the Royal House of Orange.

Incidentally, that cultivated carrot you bought or grew? The green tops are quite edible cooked. Add them to a variety of boiled dishes for flavor, or boil them separately and add them to other dishes as greenery.

The name Queen Anne’s Lace was adopted because Queen Anne of Great Britain was adept at making lace. They carried the allusion farther by saying the red flower in the middle is when she pricked her finger and a drop of royal blood fell on the flower.

Daucus is from the Greek word δαύκον (THAV-kon) meaning carrot parsnip and other similar food plants. Carota is from the Greek Καρότον ka-ROW-ton, also meaning carrot is from the Indo European word Ker, meaning head or horn. Pusillus is Latin for tiny or puny.

An excellent link for more info: http://www.foragingtexas.com/2008/08/queen-annes-lace.html

Poison-hemlock

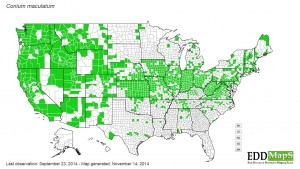

Conium maculatum

Poison-hemlock is acutely toxic to people and animals. In western Washington, it is common on roadsides, in open fields, and in natural areas. Unrelated to the native evergreen hemlock tree, poison-hemlock can be deadly; it has gained notoriety through its use in the state execution of Socrates.

Poison-hemlock can be confused with wild carrot (Daucus carota, or Queen Anne’s Lace), as with many other members of the parsley family that resemble it. It has hairless hollow stalks with purple blotches. It can get quite tall, sometimes up to 8 feet or higher. It produces many umbrella-shaped flower clusters in an open and branching inflorescence. In contrast, wild carrot has one dense flower cluster on a narrow, hairy stem, usually with one purple flower in the center of the flower cluster, and is usually 3 feet tall or less. Poison-hemlock starts growing in the spring time, producing flowers in late spring, while wild carrot produces flowers later in the summer.

Poison-hemlock is acutely toxic to people and animals, with symptoms appearing 20 minutes to three hours after ingestion. All parts of the plant are poisonous and even the dead canes remain toxic for up to three years. The amount of toxin varies and tends to be higher in sunny areas. Eating the plant is the main danger, but it is also toxic to the skin and respiratory system. When digging or mowing large amounts of poison-hemlock, it is best to wear gloves and a mask or take frequent breaks to avoid becoming ill. One individual had a severe reaction after pulling plants on a hot day because the toxins were absorbed into her skin. The typical symptoms for humans include dilation of the pupils, dizziness, and trembling followed by slowing of the heartbeat, paralysis of the central nervous system, muscle paralysis, and death due to respiratory failure. For animals, symptoms include nervous trembling, salivation, lack of coordination, pupil dilation, rapid weak pulse, respiratory paralysis, coma, and sometimes death. For both people and animals, quick treatment can reverse the harm and typically there aren’t noticeable aftereffects. If you suspect poisoning from this plant, call for help immediately because the toxins are fast-acting – for people, call poison-control at 1-800-222-1222 or for animals, call your veterinarian.

Telling Them Apart

Queen Anne’s Lace has a deadly look-alike, Hemlock. Even touching Hemlock can poison you, and ingestion means almost certain death unless treated immediately. As the toxins from the plant absorb into your system, you slowly become paralyzed, your respiratory system fails, and you die.

There are several very clear differences between Queen Anne’s Lace and Hemlock. It’s pretty easy to tell them apart once you learn what to spot, so don’t be afraid to try!

Although they both have umbrella shaped tiny white (or sometimes pale pink) clusters of flowers, Queen Anne’s Lace has a teeny tiny purple or crimson colored flower in the center of its blooms. It isn’t always there, sometimes it has already withered, or hasn’t developed yet. But if you see this, you know for sure it’s Queen Anne’s Lace.

Hemlock looks a bit different, when you get close enough to really get a good look. Though it would be hard to accurately tell the difference every time by only looking at the blooms. Thankfully, the stems are a dead giveaway.

Queen Anne’s Lace has a hairy, completely green stem.

Poison Hemlock is smooth, and has purple or black spots, or streaks on the stem.

Another identifier is the way the plants look when the blooms are dying back. Queen Anne’s Lace will fold up like a bird’s nest.

Hemlock will not fold up as it goes to seed, but will just turn brown instead.

But the REAL test is the smell. If you’ve found a flower and you are fairly certain that you’ve identified it as a Queen Anne’s Lace, the final test is to crush the stem a little then smell. If it smells like a carrot, you can know for sure that it’s Queen Anne’s Lace, and it’s safe to eat. If it stinks, or has a musty/yucky smell, go wash your hands, it’s possible that the plant is Hemlock.

http://newlifeonahomestead.com/wild-carrots-queen-annes-lace-and-deadly-hemlock/

http://www.kingcounty.gov/environment/animalsAndPlants/noxious-weeds/weed-identification/poison-hemlock.aspx

This was very helpful. I have a yard full of wild carrot. I knew it was wild carrot when I pulled it up and smelled like carrot. I came online to research and make sure it was edible and safe because I know that wild things are not always edible. I do have the poisonous one out by the road but whats in the yard so far is wild carrot. All have hairy stems and smell like carrot when pulled. Thank you for the explanation in detail.